Rev. Emily Wright-Magoon

Jan 15, 2017

OPENING WORDS

Today we honor Martin Luther King, Jr the radical.

I think it compelling to first begin with Ella Baker, a prominent civil rights activist, in part because the voices of women were too often erased from the movement, and also because Ella Baker, interestingly, criticized our need for strong charismatic leaders. Instead she worked behind the scenes for empowerment through a radically democratic process. So, while we speak today mostly of King, let us remember that, as Ella Baker said, “Martin didn’t make the movement. The movement made Martin.”

Even if segregation is gone, we will still need to be free; we will still have to see that everyone has a job. Even if we can all vote, but if people are still hungry, we will not be free …Remember, we are not fighting for the freedom of the Negro alone, but for the freedom of the human spirit, a larger freedom that encompasses all of [hu]mankind.

– Ella Baker

SERMON

Do we know the radical Martin Luther King Jr?

When he died he was mostly despised.

Two years before King was murdered, as he headed to Northern cities to address poverty, slums, housing segregation and bank lending discrimination — the Gallup Poll found that 63 percent of Americans had an unfavorable opinion of King. The FBI at the time called him “the most dangerous man in America” and regularly surveilled him. Because of his contacts with known terrorists of his day such as Nelson Mandela (!), under our current policies of the National Security Administration and Obama administration, King would have been subject to detention without trial and assassination by executive decree.

Yet today, a recent Gallup Poll discovered that 94 percent of Americans view him in a positive light.

But do we know him?

It is easy to sanitize King in order to evade his challenge to us.

MISINTERPRETING KING

Each time a black community riots, social media and the national media erupt, shaming the rioters with King’s call to nonviolence.

Yet do they know that King said “the riot is the language of the unheard”? King did believe that violence was both immoral and impractical, and yet, he never discounted the reasons for the rage at the root of riots. He said:

I contend this cry of ‘Black Power’ is at bottom a reaction to the reluctance of white power to make the kind of changes necessary.

King would reel at his words being used to silence dissent.

And which is the most commonly known of King’s speeches? “I have a dream!”

We remember King the dreamer, but rarely do we remember King the critic, the rabble-rouser.

What are the most remembered lines from that speech?

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.”

This quote is regularly lifted from its context to promote color-blindness, the potential for reverse racism, the belief that because slavery ended and the civil rights era happened, and Obama is President, that we now live in a post-racial society and need not talk anymore about white privilege or the need for affirmative action or reparations.

King would be horrified at this use of his words. He said white people’s belief in the fairness of America “is a fantasy of self-deception and comfortable vanity.”

THE DREAM IS NOT YET REAL

He declared then and would certainly declare now that his dream is not yet real – not even close! Yes, race is culturally constructed – and that’s the problem. We do not yet live in a time where skin color does not matter. We have not yet even repaired the damage done, we have not yet accounted for the many privileges given to generations and generations of white Americans, and the many burdens and roadblocks set before people of color. Slavery is only two to three generations in the past! And even after slavery ended, the “Jim Crow” laws that followed relegated black people to second-class citizenship for nearly a century.

This photo was taken 25 years after the “end” of slavery. These Black boys are all in a forced labor camp, working for free, often for 6 days a week. Many were arrested and convicted for “loitering” & “vagrancy” or “speaking loudly to a white woman.”

While people seen as white were given low interest loans, or land grants, or free education (those privileges inevitably trickling down as greater opportunities for their children), the grandchildren and great grandchildren of slaves experience the trickle down of poverty, of trauma.

This can be said of many of the people of color in our country – think of Native Americans. Who would honestly think that their high rates of alcoholism and suicide are solely due to their supposed flaws and not the inheritance of oppression?

And I don’t mean to only highlight the ways people of color have struggled – they have certainly persevered! Under unimaginable circumstances they have garnered strength of character, courage, deep resilience. Mexican and Latin American people, for example, are some of the most hardworking people I have known – if only our country wasn’t set up to demand such sacrifice from them.

The radical King believed that in order for there to be true racial and economic justice, there must be “a radical redistribution of political and economic power.” How much of us would be comfortable with redistribution?

Georgetown University was in the news last year for taking steps to atone for its part in slavery. In 1838, to save itself from going under, Georgetown sold 272 slaves – humans – worth about $3.3 million in today’s dollars. Last year the Georgetown announced it would atone by offering a formal apology, creating an institute for the study of slavery, erecting a public memorial, and offering preferential admission to the descendants of those 272 slaves. Critics say this is a step in the right direction but does not really qualify as reparations. Memorials and apologies only do so much. Even giving preferential treatment to slaves’ descendants in the application process relies on those young people’s ability to achieve a certain degree of academic success, know that they were descendants of Georgetown slaves, and be able to afford college.

Reparations become an even more complicated issue when you realize our country continues to profit off of people of color.

The prison industrial complex is a web of government and for-profit entities that profit off prisoners, 70% of whom are people of color, most arrested for petty drug crimes, most often marijuana. Many companies whose products we use daily have found that prison labor can be as profitable as third world labor. IBM, Motorola, Texas Instruments, Honeywell, Microsoft, Boeing, Revlon, Nordstroms, Chevron, Victoria’s Secret, and more use cheap prison labor.

King saw all of this on its way.

He confided in his friend Harry Belafonte: “You know, we fought long and hard for integration…But I tell you, Harry, I’ve come on a realization that really deeply troubles me. I’ve come to the realization that I think we may be integrating into a burning house.”

THE THREE EVILS

Rampant poverty and the war in Vietnam had galvanized his analysis of the issues.

He began speaking about the three evils of society: not only racism, but also materialism and militarism. King was radical because he saw to the root of problems. That’s what radical means – root. So the radical King called for a “revolution of values” from a “thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society.”

He came out against the Vietnam war when it was incredibly unpopular to do so, even among black leaders. Before he died, he was planning the “Poor People’s Campaign” a mass march and occupation of DC until the US government granted poor people of diverse backgrounds an “Economic Bill of Rights.”

The King that we narrow down to concerns about race was also the King concerned with war, with exploitation, with poverty in any race.

He told this story of talking with the white wardens when he was in jail in Birmingham:

The second or third day [we got down] to talk[ing] about where they lived, and how much they were earning. And when those brothers told me how much they were earning, I said, “Now, you know what? You ought to be marching with us. You’re just as poor as Negroes.” And I said, “You are put in the position of supporting your oppressor, because through prejudice and blindness, you fail to see that the same forces that oppress Negroes in American society oppress poor white people. And all you are living on is the satisfaction of your skin being white, and the drum major instinct of thinking that you are somebody big because you are white. And you’re so poor you can’t send your children to school. You ought to be out here marching with every one of us every time we have a march.

King’s vision of the beloved community was truly different than the status quo, then and now.

The black author Cornel West says that King would be dismayed by much of Obama’s presidency. West says, “The dream of the radical King for the first black president surely was not a Wall Street presidency, drone presidency, and surveillance presidency.”

The morning of the day when King was killed, he had called his church to give them the title of his sermon planned for that Sunday: “Why America May Go to Hell.” Two months earlier he had preached about how America would go to hell if we did not use our vast wealth to create justice and peace instead of poverty and violence.

A RADICAL FAITH

But the way King was truly radical was in his spirituality.

The deep wells of his faith gave him the power to be unpopular, to skirt risk, to face death at every turn.

His faith was in radical love. Not passive love, but active courageous love. Cornel West says:

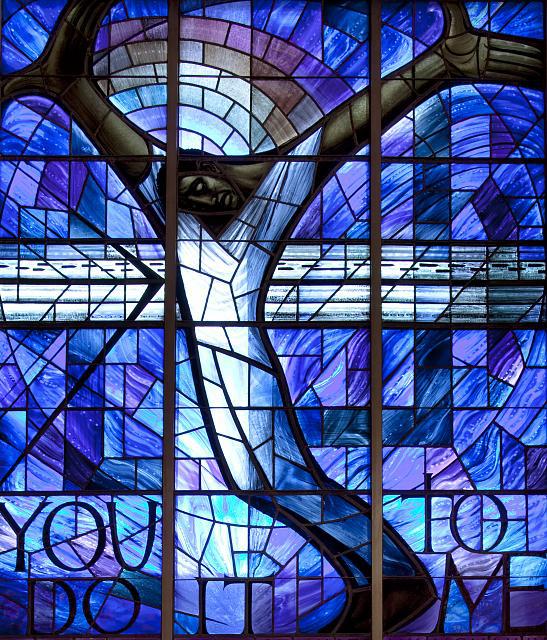

King understood radical love as a form of death – a relentless self-examination in which a fearful, hateful, egoistic self dies daily to be reborn into a courageous, loving, and sacrificial self.” For King, “this radical love flows from an imitation of Christ, a response to an invitation of self-surrender in order to emerge fully equipped to fight for justice in a cold and cruel world of domination and exploitation. There is no radical King without his commitment to radical love.

((Carol Highsmith’s photo of the Wales window at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church.Credit: The George F. Landegger Collection of Alabama Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith’s America, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. [LC-DIG-highsm-05063]))

((Carol Highsmith’s photo of the Wales window at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church.Credit: The George F. Landegger Collection of Alabama Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith’s America, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. [LC-DIG-highsm-05063]))

Nonviolence is a power rooted in love. And King said of Love:

“Love, agape, is the only cement that can hold this broken community together.”

The further way his faith sustained him was the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice.

King said this was the only way nonviolent resistors could accept suffering without retaliation: “He knows that in his struggle for justice he has cosmic companionship. …[Whatever we call it]…” (he left room for atheists and Hindus and agnostics here) “…there is a creative force in this universe that works to bring the disconnected aspects of reality into a harmonious whole.”

I’ll close with this story in Rev. Dr. King’s words, from his sermon “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” delivered on the eve of his assassination:

I remember in Birmingham, Alabama, when we were in that majestic struggle there, we would move out of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church day after day. By the hundreds we would move out, and Bull Connor would tell them to send the dogs forth, and they did come. But we just went before the dogs singing, “Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me ‘round.” Bull Connor next would say, “Turn the fire hoses on.” …[But] there was a certain kind of fire that no water could put out. And we went before the fire hoses. …And we’d just go on singing, “Over my head, I see freedom in the air.” And then we would be thrown into paddy wagons, and sometimes we were stacked in there like sardines in a can. And they would throw us in, and old Bull would say, “Take ’em off.” And they did, and we would just go on in the paddy wagon singing, “We Shall Overcome.” And every now and then we’d get in jail, and we’d see the jailers looking through the windows being moved by our prayers and being moved by our words and our songs. And there was a power there which Bull Connor couldn’t adjust to, and so we ended up transforming Bull into a steer, and we won our struggle in Birmingham.

– Rev. Emily Wright-Magoon